Q: My husband was going to pick up our child from school to get to an appointment. I was, unusually, working at home that day.

The time came when I thought he should be making noises to go, but he was in a meeting. I know I tend to leave earlier than he does, so I just told myself to let him do it his way. But then I heard him get on a conference call and he was obviously presenting info and was actively talking.

Do I interrupt the call? Do I just sit there and let things play out, knowing our kid will be sitting at school and I will get a call in ten minutes asking where we are?

I ended up texting my husband, waiting five minutes to no response, and then, about five minutes before we were supposed to be at pick up, texted him that I was going, and left to get our child.

How can I not overfunction for another person when there is a third party involved who will feel the fallout?

A: What a great observation of the patterns at work in a family. When we get more objective about self and others, we’re governed a little less by the anxiety of the moment.

Let me throw some questions at you.

First, how would you define what it means to manage yourself thoughtfully in this kind of dilemma? Because in my mind, it’s not so much the decision you make as it is how you manage yourself in it. You could have two different people make the same choice (i.e. picking up your kid, not picking up your kid, interrupting the meeting, etc.) but one could be operating with more maturity, and less reactivity, than the other. How do you believe in your choice enough to activate it in the most thoughtftul way?

Second, what’s your theory about how systems become more flexible? How do they evolve? How do people begin to feel more comfortable with responsibility, and how do we sometimes get in the way of that flexibility?

I think systems become more flexible when people do exactly what you’re doing. They start to observe the automatic-ness of people’s behaviors, the tendency of some people to become over-responsible or under-responsible. And then they ask themselves, “How do I get clearer about what my responsibilities are and aren’t? What is my position in this situation?”

We can say we’re stepping back, but we often still have an intense focus on another person’s functioning. That intensity doesn’t increase the flexibility. I observed this just this morning while my husband was fixing my daughter’s hair. I can guarantee you that everyone felt my reactivity. Talk about an emotional workout, even when the stakes are incredibly low! If I can manage myself, everyone benefits. If not, sure, her hair might look a little nicer. But what’s the cost? And is it worth it? These are the questions you have to ask when you intervene.

Anxiety distorts the stakes. It makes us overestimate, or underestimate, what the cost will be. If I’m not managing my anxiety, I am acting as if my kid’s sub-optimal hair day is going to tip the balance for her entire social life. And in other situations, I may be anxiously avoiding something that is actually important.

It’s about the anxiety, and what you do with it. It’s not the decision—it’s the degree to which that decision is bound by the automatic patterns that govern the family.

My suggestion is to go back a generation or two, and think about how these patterns played out. We’re often too close to the problem in our nuclear families to see the patterns and the stakes. I think about my own family members, who were always first in the pick up line. It might have done me some good to have been forgotten a few times! Other people might have had the opposite challenge.

It’s a hell of a gift for a kid to have a parent who is doing this kind of thinking. Who is making themselves, and their maturity, the project. It’s a gift to have a parent who is willing to tolerate the discomfort that comes from letting others be responsible for themselves. A gift to have a parent who tries something, and isn’t so hard on themselves when they need to pivot.

News from Kathleen

Appreciate content like this? Consider becoming a paid subscriber, to receive additional newsletters, worksheets, and other resources.

*GOODREADS GIVEAWAY for True to You. Enter here to win 1 of 50 copies!

Want a signed, personalized copy of my next book, TRUE TO YOU? You can preorder it from my neighborhood bookstore, East City Bookshop. I’ve also created a digital bonus workbook for newsletter subscribers who preorder. More on that soon!

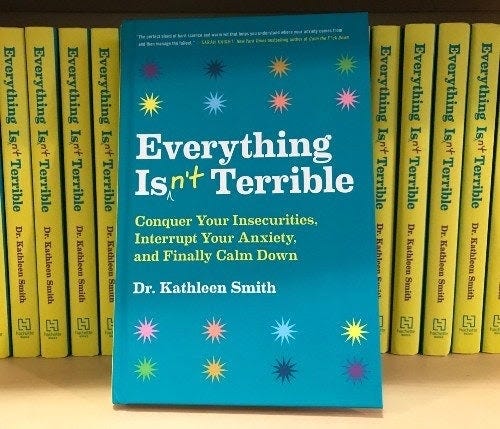

Want to read more of my writing? Get my book, Everything Isn't Terrible, from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or your local bookstore (best option).

Want a free anxiety journal with the book? Calming Down & Growing Up: A 30 Day Anxiety Journal includes thirty daily prompts to help you reflect on and respond to your anxious behaviors. To receive a copy, just email me your receipt of Everything Isn’t Terrible.

Email me if you’re interested in Bowen theory coaching or want me to speak to your group or workplace. Follow me on Linkedin, Facebook, or Instagram.

Want to learn more about Bowen theory? Visit the Bowen Center’s website to learn more about their conferences and training programs.